Title & author

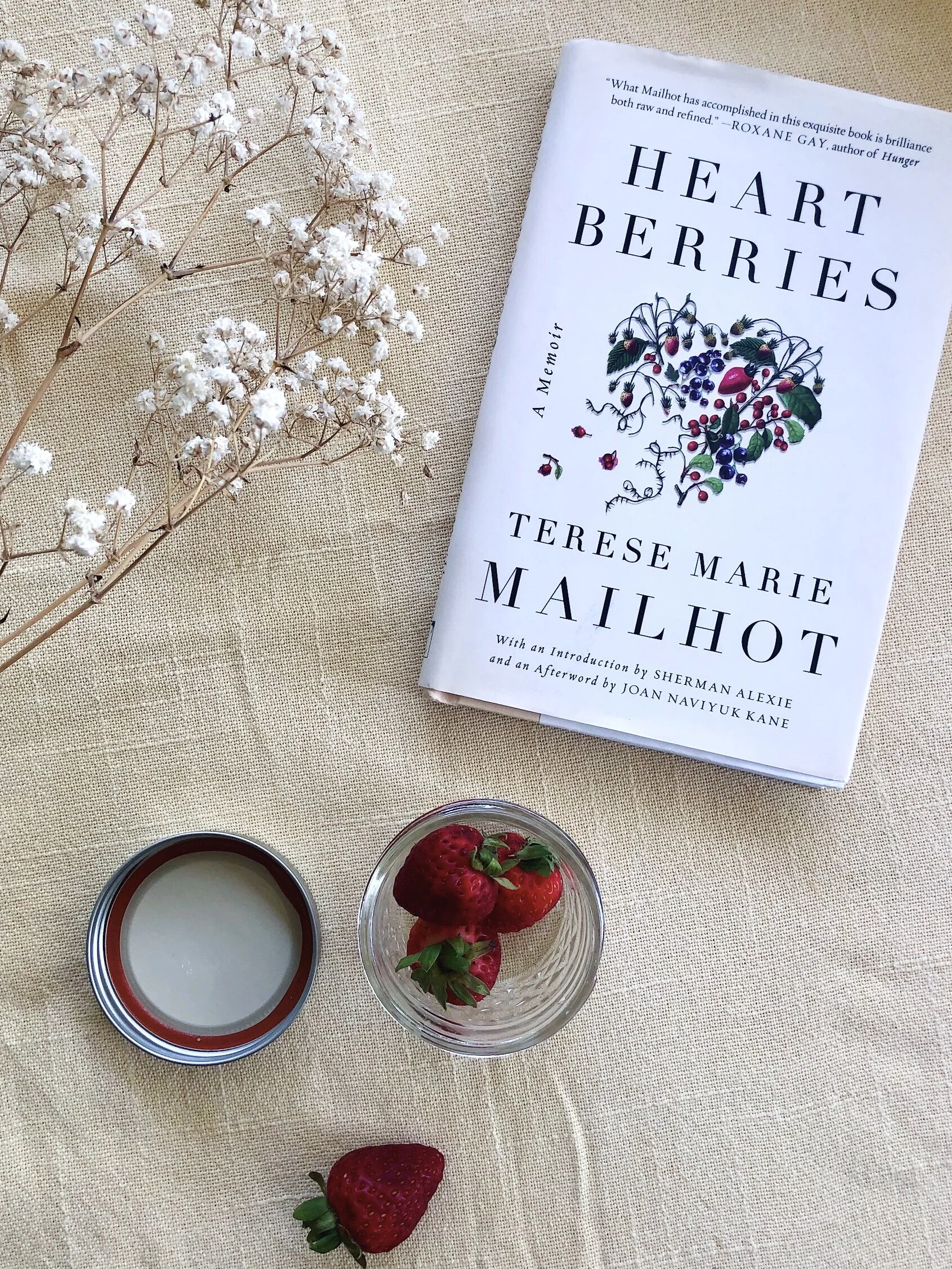

Heart Berries by Terese Marie Mailhot

Synopsis

Largely written during her time at a behavioral health hospital, Terese Marie Mailhot’s Heart Berries details the various events that have built up over her lifetime to lead her here, as well as what she goes on to face afterwards. Her writing exposes the unity found in pain and beauty and looks at the concept of self through multiple lenses, including gender, mental health, race, and more. All the while, she refuses to allow for the interpretation of her writing as existing for anything other than her own need to discover the truth.

Who should read this book

Fans of Maggie Neslon and Kathleen Alcott

What we’re thinking about

What “greats” have been erased from, or never considered for, America’s literary canon?

Trigger warning(s)

Physical violence, sexual violence, substance abuse, eating disorders, self-harm, slurs, abandonment, sexism, mental health, racism

“My story was maltreated,” Terese Marie Mailhot begins, the four words launching her memoir Heart Berries (Counterpoint Press, 2018), a story of existence and exploration (Mailhot, 3). Written in part as a letter after committing herself to a behavioral health hospital, Mailhot details the various events that have built up over her lifetime to lead her here, as well as what she goes on to face afterwards. Her inquisitive writing exposes the unity found in beauty and pain and looks at the concept of self through multiple lenses, including gender, mental health, race, and more. All the while, she refuses to allow for the interpretation of her writing as existing for anything other than for her own need to discover the truth.

Rooted in questions and self-reflection, Mailhot’s memoir embodies exploration of self and of others. In doing so, she emphasizes that the memoir exists for her own purposes-- not for white narratives or complexes, nor for the “Native American community”-- but simply for herself and women who have a shared story. “Do you still love me? I still want you,” and “Can’t you wash me? Or hollow me out for good?” are just examples of the questions she asks of her lover, Casey (17, 99). Throughout, Mailhot utilizes questions to hold a mirror up to their relationship, searching for answers. She questions her mother, “not trying to make excuses” for her actions, but still attempting to understand how “she did fall” (37). And she questions herself, unsure “if what [she] felt was authenticity, or a disease that would overtake” her (69). Mailhot confronts the actions of those who have shaped her life, searching for answers through writing.

Yet in all the pain and questions that go unanswered, there is beauty, particularly in Mailhot’s descriptions that reinforce the book’s existence as something for her own needs. “You seemed engaged by my dysfunction because you are a writer and not because I had experienced it,” she writes (34). She highlights the overarching issue with the colonization of literature and the fetisization of Indigenous narratives (and white expectations of Indigenous narratives): that whiteness revels in the experiences of “the other” as something of fascination, but without true acknowledgement. “As an Indian woman, I resist the urge to bleed out on a page, to impart the story of my drunken father...It is my politic to write the humanity in my characters, and subvert the stereotypes. Isn’t that my duty as an Indian writer? But what part of him was subversion?” (82). Mailhot grapples with the expectations from both white and Native readers; she does not want to fuel stereotypes. However, “I’m a woman wielding narrative now, weaving the parts of my father’s life with my own” (86). Even more importantly than the expectations of anyone else, is the need to narrate her truth, the need to narrate just for her own sake. And in telling her story for herself, she will display the parts of her father, the good and the bad, that shaped her into the artist she becomes.

But can we as readers accept that this story is not for us? “Sometimes I hide my empties because I don’t want to be a drunk Indian. I do get drunk, and I am Indian, but not both,” she writes (117). Can we read this text without sexualizing, stereotyping, limiting Mailhot? She challenges the reader to do so, knowing “it was a hundred years of work for my name to arrive here, where I can name my pain so well that people are afraid of the consequences and power” (119). Mailhot’s memoir refuses to accept the history or present of the tokenization, mistreatment, and overlooking of Indigenous stories. She calls on us to acknowledge her strength as a writer, and not “simply” as an Indigenous voice, but amongst literature’s greats. Heart Berries opens a conversation about the exploration of identity. Mailhot writes not because of her Indigenous heritage, but through the lens of, a distinction that enables her to write for her own purpose, to ask the questions she needs to ask, and to fight against erasure.

“I was part of a continuum against erasure, I told myself. My body felt stronger when I embraced it. I felt connected to a lineage of women who had illustrated their bodies and felt liberated by them.”

Join in

Contribute your thoughts by using the “Leave a comment” button found underneath the share buttons below. Answer one of these questions, ask your own, respond to others, and more.

What role does the concept of “family” play in the text?

Mailhot in an interview said that originally she did not plan to write a memoir. How does Heart Berries as a memoir shape our reading, as opposed to a piece of fiction? Or, more generally, how does a memoir shape our understanding, versus fiction?

Please note that all comments must be approved by the moderator before posting. We reserve the right to deny offensive or spam-related commentary. And, for the wellbeing of our BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, and/or disabled-identifying community members, please respect the personal capacity to address questions on certain topics. We encourage you to search for the answer in a great book or online instead. Thank you!